That is an version of the revamped Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly information to the most effective in books.

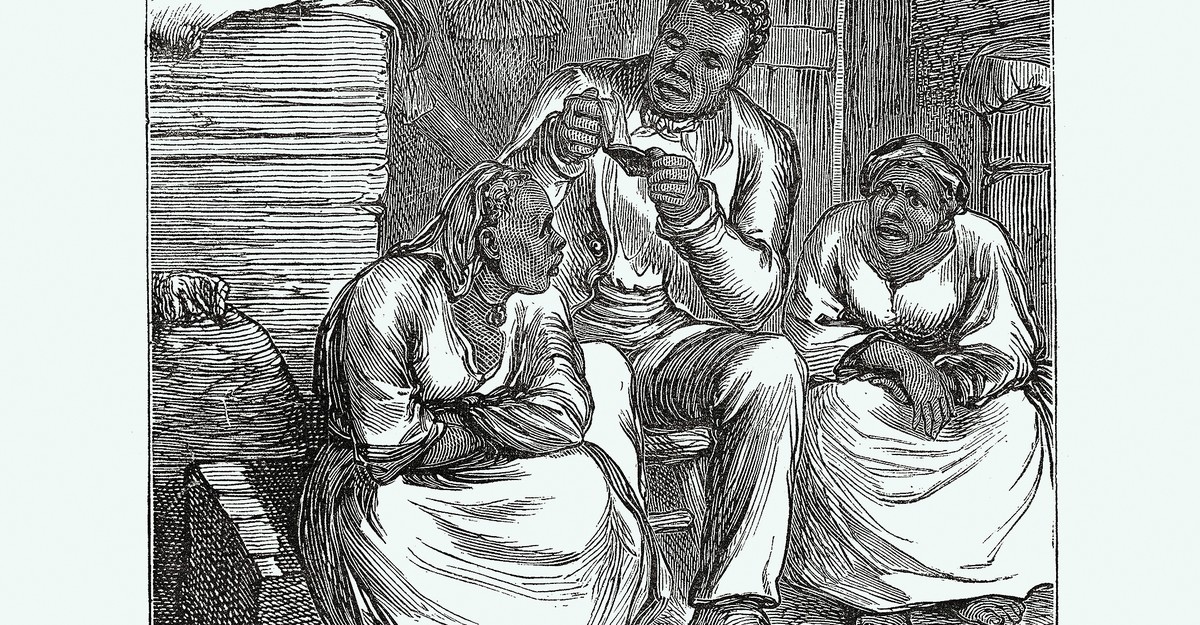

, first printed to colossal success in 1852, has been in reputational free fall ever since. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel concerning the trials of an enslaved man named Tom who accepts his struggling with Christian equanimity proved a boon to the abolitionist trigger, although its precise depictions of Black folks skimp on offering them with a lot humanity. Even in its time, the guide was vulgarized by way of stage diversifications that lowered Stowe’s story to minstrelsy and her characters to caricatures. Immediately, a piece that did a lot to shake white northerners out of their complacency is remembered largely as a slur. However in for The Atlantic’s October difficulty, Clint Smith shocked himself by discovering the unique energy of the guide—together with what stays so restricted and prejudiced about it. His article uncovers the story of Josiah Henson, the “unique” Uncle Tom, Stowe’s real-life inspiration for the character. In his 1849 memoir, Henson described what it was prefer to be an overseer on a Maryland plantation and all the ethical compromises he needed to make to outlive slavery. Changing into acquainted with Henson’s story additionally gave Smith a brand new perspective on Uncle Tom’s Cabin. I talked with Smith about this side of his essay, and the way he was in a position to brush a lot gathered mud off the guide.

First, listed here are three new tales from The Atlantic’s Books part:

Smith spoke with me from South Korea, the place he was doing analysis for his new guide. This interview has been condensed and edited for readability.

Gal Beckerman: What was your sense of Uncle Tom’s Cabin earlier than you opened it up once more for the essay—or was it perhaps the primary time you learn it?

Clint Smith: I’d solely learn excerpts in highschool. I’d by no means learn the guide in full. However most of my relationship to the guide was via James Baldwin’s essay about it. He had written it in 1949; he was simply 24. And this was his first large essay, the one which places him on the nationwide scene. And he simply actually—

Beckerman: He was not a fan.

Smith: He was not a fan of Harriet Beecher Stowe, of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He makes the case that it’s extra a political pamphlet than a guide. That it’s a reductive try at literature that renders the characters as two-dimensional. And it’s not artwork a lot as it’s a part of an ideological undertaking. So I used to be primed for that, going into the studying of the guide. And as I’m making my manner via I’m observing numerous the moments by which Stowe stereotypes Black folks, by which the white characters are introduced as having extra humanity, extra complexity than the Black characters. However there are also components of the guide that I assumed have been actually fascinating in the best way they introduced the ethical complexity of slavery in ways in which maybe no different author was doing in that manner at the moment.

Beckerman: Did this alteration your final evaluation of the guide?

Smith: I feel my relationship to the guide, by the point I acquired to the top of it, was a kind of a each/and. On one hand, you already know, the best way that a number of the Black characters are introduced is basically unsettling. She has this factor the place she breaks the fourth wall loads. And people are the moments that I assumed have been really imbued with essentially the most stereotypes. However when she’s simply letting the characters simply be human beings or as shut as attainable, you’re seeing a number of the nuance.

Beckerman: You talked about within the piece that there have been methods by which the guide confirmed the white characters trapped in supporting slavery regardless of themselves, or understanding that this was an evil that they have been concerned in however going together with anyway, not figuring out how one can extract themselves.

Smith: Precisely. And I assumed that these scenes have been actually beneficial, as a result of I feel they converse to a really human factor. Clearly, there are gradations of it. However all of us do, all of us take part in issues that aren’t aligned with our values. And when you perceive that the style Harriet Beecher Stowe was working in was very a lot a kind of common fiction—it was business fiction, in the best way that we sort of perceive it at the moment—it’s outstanding how the message reached the lots. Given the expertise of the day, it went viral in a Nineteenth-century context. And it served as a catalyst to dialog and discussions and consciousness that merely weren’t occurring. And so I feel you’ll be able to look at it on a literary degree and have many critiques. And I feel you’ll be able to look at it on a historic degree and acknowledge that amid its shortcomings, it performed an infinite function in shaping the general public consciousness of the mid-to-late Nineteenth century. You’ll be able to’t actually overstate the affect that it had on our society.

Beckerman: What concerning the Uncle Tom stereotype? You discuss within the piece about that being one of many legacies of this guide—not even the story, however simply the idea of an Uncle Tom. Did you’re feeling that was additionally sophisticated by the precise character if you encountered him?

Smith: A part of what occurred is that I spotted that my understanding of Uncle Tom, or what an Uncle Tom is, was formed extra by all the things that adopted the publication of the guide than the character itself. As I write within the piece, there have been no copyright legal guidelines when Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote this guide. And so there have been … many performs that have been created with out her permission, or with out her enter. And a few folks tried to remain true to the essence of the guide and the characters. However there have been many individuals who turned Uncle Tom’s Cabin right into a minstrel present, and turned Uncle Tom right into a minstrel. However within the guide, Uncle Tom—although in some ways, he’s not given the kind of texture and complexity as a number of the white characters—he’s nonetheless somebody who’s form and delicate, and who, towards the top of the guide, refuses to surrender the placement of two Black girls who’re attempting to flee, and is in the end overwhelmed and killed for it. And so, in so some ways, he’s a martyr, which could be very totally different from what the time period Uncle Tom has come to imply at the moment. It has change into this slur, even inside the Black neighborhood, that individuals use towards each other to point that somebody is a sellout, that somebody is engaged on behalf of white folks fairly than their neighborhood. Which once more, is the alternative of who Uncle Tom, the character within the guide, was—somebody who sacrificed his life to avoid wasting the lives of enslaved of us who have been attempting to flee.

Beckerman: That’s additionally a perform of virality, when an inventive work will get taken out of the arms of its creator. However Josiah Henson’s autobiography: What was the expertise of studying that like, after studying Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Had you recognized about it earlier than?

Smith: No, I’d by no means heard of Josiah Henson. I’d by no means learn or heard of his guide. And I’m somebody who spent six years writing a guide on the historical past of slavery. However once I did encounter him, and encountered his guide, I used to be simply left questioning, Why didn’t I learn this in class? It could have been such a beneficial useful resource for me, and I feel it might be a beneficial useful resource for therefore many lecturers. As a result of once we find out about Harriet Tubman, once we find out about Frederick Douglass, it’s a part of an effort to withstand the pathology, the sensation of despair, that exists among the many historical past of slavery—of 250 years of being subjected to ubiquitous violence and oppression and surveillance. After which we get to their tales, and they’re emblematic of the sense of resistance that exists inside the Black neighborhood. I feel that that’s so necessary. I feel, although, if these are the one varieties of tales of resistance that we get, that we inadvertently achieve a distorted sense of what the expertise of slavery was like for the overwhelming majority of individuals. And I feel the worth of Josiah Henson’s guide is that he’s a profoundly imperfect individual, in the best way that all of us are. I imply, he does his finest to be a great individual—he’s a person of religion, a person of conviction, a person who wakes up every single day and tries to do the correct factor on behalf of his family members, on behalf of his neighborhood. And he additionally does numerous issues that he later regrets. He does numerous issues that he later is ashamed of, and he decides after which he’s like, I don’t know if that was the correct resolution. And he tries to work in the most effective curiosity of each his enslaver and the enslaved folks round him when that’s an inconceivable factor to do, given the system. I simply suppose that that’s extra reflective of the kind of ethical complexity of the establishment and the place it put folks in than another account of slavery that I’ve learn.

Beckerman: Do you suppose there’s a context inside which you’ll think about youthful folks specifically studying Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Is that also a guide that ought to be opened up and understood? How excessive ought to the guardrails be for any individual coming to it at the moment?

Smith: I feel it could possibly be actually beneficial to learn it alongside an educator who understands the kind of blended bag that it’s. I’m not somebody in any respect who believes that just because a guide presents folks in a manner that feels unsettling to us we shouldn’t learn it. If something, I feel it affords a chance to interrogate the best way that any individual has written it and to wrestle with a number of the issues that I’m wrestling with in my piece. What I got here away with after studying the guide is that Harriet Beecher Stowe was genuinely attempting to do one thing actually necessary and one thing that, frankly, had not been achieved within the mid-Nineteenth century. And in some ways, she succeeded in that. She wrote this guide that made white folks, notably white folks within the North, conscious of slavery in ways in which they merely had by no means been. And it additionally affords the chance to interrogate: Why did they should learn that guide versus a number of the slave narratives that already existed? Why have been these folks extra inclined to imagine the tales of a white lady writing about this than the tales of Black individuals who skilled it themselves? And it could possibly be actually generative to learn that guide alongside Josiah Henson’s memoir, specifically, to be able to put the 2 in dialog with each other, to see what the variations have been, what the similarities are, and to look at why one in every of these books is extra common than the opposite. I used to show high-school English in my earlier life, and I’d like to spend a couple of weeks with college students doing precisely that: studying the memoir and the guide.

What to Learn

, by Jason Lutes

In September 1928, two strangers meet on a practice headed into Berlin: Marthe Müller, an artist from Cologne on the lookout for her place on the planet, and Kurt Severing, a journalist distraught by the darkish political forces rending his beloved metropolis. Lutes started this 580-page graphic novel in 1994 and accomplished it in 2018, and it’s a meticulously researched, beautiful panoramic view of the final years of the Weimar Republic. The story focuses most attentively on the lives of atypical Berliners, together with Müller, Severing, and two households warped by the rising chaos. Sure panels even seize the stray ideas of metropolis dwellers, which float in balloons above their heads as they journey the trams, attend artwork class, and bake bread. All through, Berlin glitters with American jazz and underground homosexual golf equipment, all whereas Communists conflict violently with Nationwide Socialists within the streets—one celebration agitating for staff and revolution, the opposite seething with noxious anti-Semitism and outrage over Germany’s “humiliation” after World Struggle I. On each web page are the tensions of a tradition on the brink. — Chelsea Leu

Out Subsequent Week

📚 , by Susie Boyt

📚 , by Ismail Kadare

📚 , by Dan Ariely

Your Weekend Learn

The private-equity agency Kohlberg Kravis Roberts introduced that it might purchase Simon & Schuster. As a result of the agency doesn’t already personal a competing writer, the deal is unlikely to set off one other antitrust probe. However KKR, notorious as Wall Avenue’s because the Eighties, could go away Simon & Schuster workers and authors craving for a 3rd alternative past a multinational conglomerate or a strong monetary agency. “It could be a keep of execution, however we should always all be frightened about how issues will take a look at Simon & Schuster in 5 years,” says Ellen Adler, the writer on the New Press, a nonprofit centered on public-interest books.

Whenever you purchase a guide utilizing a hyperlink on this publication, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.