When the O. J. Simpson verdict was announced, I was a junior at Michigan State University. At the time, I was the managing editor of my college newspaper, The State News, so I didn’t have the luxury of reacting emotionally one way or the other. I had the responsibility of figuring out how our publication was going to present to 40,000 students this stunning outcome to what many had called “the trial of the century.”

But as I watched the verdict on the TV in our college newsroom, I immediately understood why some of the white staffers on the paper reacted with visible disgust—and why a lot of my Black friends felt relieved, even joyous, that Simpson had been found not guilty of murdering his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ronald Goldman. Although, back in 1995, everyone was aware of the racial divide in this country, the trial provided stark evidence of just how sharp it was.

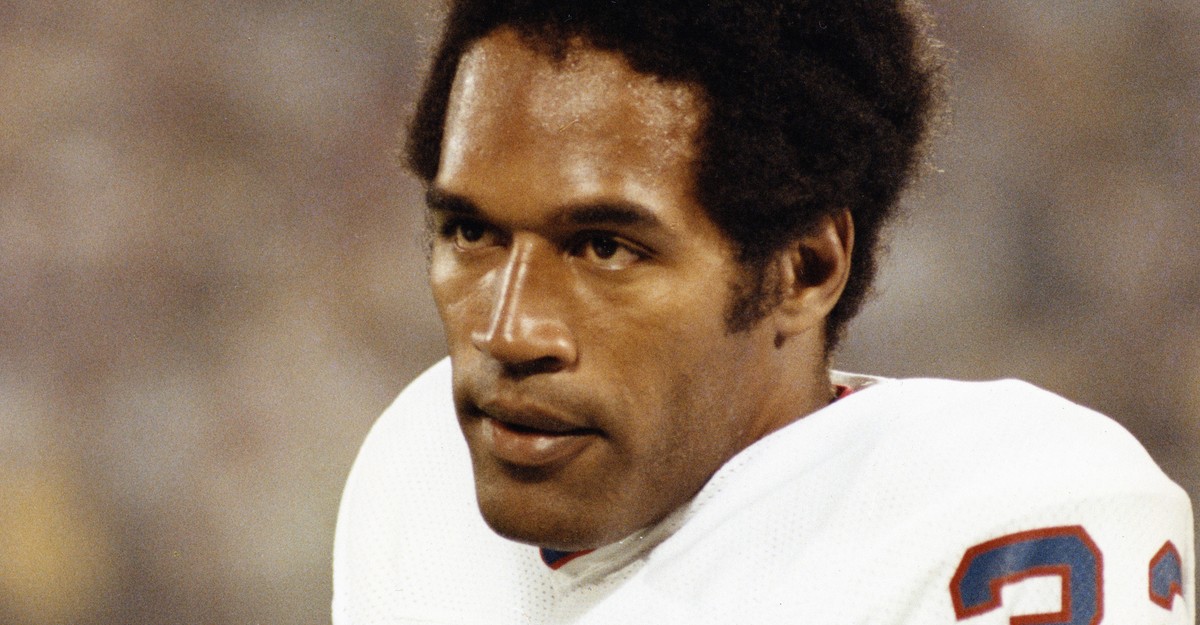

As a student journalist, I understood that this was a significant piece of the story. The predominantly African American jury’s not-guilty verdict seemed inseparable from the deep distrust Black people had in law enforcement, but I did not see it as a moment to celebrate. Simpson’s football achievements had received due recognition—he was a Heisman Trophy winner and an NFL Hall of Famer. But athletic prowess aside, he had long since distanced himself from the Black community. Purposely so, and he seemed to revel in his exceptional proximity to white America. To my mind, the message that the verdict sent about Black skepticism toward the criminal-justice system couldn’t be detached from its far-from-ideal messenger.

When Simpson’s death was , the racial divide that the trial had exposed came back to the surface. The CNN contributor Ashley Allison, a policy adviser for former President Barack Obama who had also worked on President Joe Biden’s campaign, that the Simpson trial “represented something for the Black community” because it put a spotlight on the racial inequity that Black people commonly face in the criminal-justice system. Marc Lamont Hill, an anthropology and urban-education professor and a media commentator, summarized Simpson’s career in this way: “O.J. Simpson was an abusive liar who abandoned his community long before he killed two people in cold blood. His acquittal for murder was the correct and necessary result of a racist criminal legal system. But he’s still a monster, not a martyr.” Both were by right-leaning outlets. Despite a steady supply of evidence that the criminal-justice system does indeed treat Black people differently, pointing this out in the context of the Simpson case still brings condemnation for Black advocates who do so.

Among other reactions to the news of Simpson’s death, Torrey Smith, a former NFL player who is also Black, for relying heavily on Simpson’s courtroom photos in the coverage of his death—in his view, thus relitigating Simpson’s acquittal. Meanwhile, Caitlyn Jenner, whose ex-wife, Kris Jenner, was best friends with Nicole Brown Simpson, “Good Riddance” on her X account. The fact that we’re still arguing about O.J. shows that we haven’t come as far as we should have, in part because too many white people misunderstand the reaction among many Black people to his acquittal in the first place.

What they miss is that if Black people cared about Simpson’s trial, and the way it exposed cracks in the criminal-justice system, they never cared much about Simpson the man. As a sports journalist, I’ve talked to countless people over the years about these questions. I’ve found that Simpson was not the cultural fixture in the Black community that some white people assumed he was, and apparently continue to assume he is. As Simpson people, “I’m not Black, I’m O.J.” I took Simpson at his word and so did many others.

By comparison, such notorious abusers as Bill Cosby, R. Kelly, and have a much stronger cultural hold. All three have been accused of abusing women (in Kelly’s case, actually convicted), yet some ambivalence persists in the Black community about their status and their work—each still has or who seem willing to either stick by their icon or judgment.

With Simpson, no such relationship exists. Just because many Black people believe that his acquittal was the proper verdict—and, yes, some celebrated when it came down—doesn’t mean that Simpson was our guy. And who was that guy? In 2008, of multiple charges relating to an armed robbery in which he and associates broke into a Las Vegas hotel room to retrieve items that he claimed had been stolen from him. Simpson was sentenced to 33 years in prison but served about nine before .

Some people may have seen his conviction and imprisonment in that case as some sort of payback for his murder acquittal, but—in my circles, at least—practically no one claimed Simpson as a misunderstood political figure, let alone a hero. With his career as a sports commentator, his appearances in ads, and his movie roles, O.J. achieved an almost unique level of acceptance—as a celebrity, he arguably meant more to white America than he did to Black America. So if anything, in my experience, some white Americans seemed more upset than Black people ever were that Simpson wasn’t who they thought he was.

Put simply, he was a once-great athlete who turned out to be a terrible person. The mingled legacy of his celebrity and criminality is that his murder trial forced our country into difficult conversations—particularly about domestic violence and how, regardless of race, fame can protect people like Simpson from consequences. Above all, though, Simpson’s death is a reminder of how far this country still has to go to heal the racial rift that his murder trial so mercilessly exposed.